Telling the Bees: Unearthing the Bizarre 19th-Century Death Superstition

Imagine this: it’s the 1800s, gas lamps flicker, and news travels slower than, well, a bee in January. Someone in your community passes away. What’s the next logical step? You might think of notifying relatives, planning the funeral… but if you were living in certain parts of Europe or 19th-century America, particularly stretching from New England down towards the Appalachians, there was another crucial task. A task that involved… whispering secrets to your beehives. Wait, what?

Yep, you read that right. This wasn’t some quirky little aside; it was a full-blown death superstition known as “telling the bees,” and it was taken seriously. We’re talking about families going to great lengths to inform their bees – their insects – about a death in the household, especially if the deceased was the beekeeper themselves. But why? And what in the world were they actually supposed to do? Let’s uncomb this sticky situation, shall we?

The Buzzkill Belief: Why “Telling the Bees” Was a Must

So, what was the big deal? Why all the hushed tones and draped hives? The core belief was surprisingly straightforward, if a tad dramatic: if you failed to inform your bees of a death, well, bad things would happen. Really bad things.

The most common fear? The bees would die. Imagine the horror! All that hard work, all that sweet, sweet honey production… gone, just because you forgot to share some somber news. Another equally terrifying (at least, to a 19th-century family reliant on honey) possibility? The bees would up and leave. Just pack their tiny bags, abandon their hives, and swarm off in search of… well, who knows? Perhaps a beekeeper who was better at keeping them in the loop. Can you picture the tiny bee suitcases?

For families who relied on beekeeping, this wasn’t just about sentimentality for their buzzy buddies. Honey was a valuable commodity. Sweetening food, making mead, medicinal uses – it was a big deal. Losing a hive was an economic loss they desperately wanted to avoid. Hence, “telling the bees” became less of a suggestion and more of a… well, insurance policy against bee-related financial ruin.

Black Crepe and Funeral Cake: The Ritual of Bee Notification

Okay, so you had to tell the bees. But how exactly did one go about informing a colony of insects about the grim reaper’s latest visit? It wasn’t exactly like sending out a mass text, was it? (Thank goodness for no 19th-century bee texting, can you imagine?) No, “telling the bees” was a whole ritual, a somber little performance acted out for the benefit of, well, bees.

Here’s the typical playbook:

- The Messenger: Someone, often a child or a designated member of the household, was tasked with delivering the news. This wasn’t just a casual chat; it was a solemn duty.

- The Announcement: The messenger would approach the hive, often in hushed tones (were the bees eavesdropping? We may never know). They’d then, quite literally, tell the bees about the death. The wording varied, but the gist was always the same: “[Deceased’s name] is gone,” or “Mistress/Master is dead.” Direct, to the point, hopefully bee-digestible.

- The Black Draping: After delivering the verbal message, the hives would be draped in black crepe. Think of it as tiny bee mourning attire. Black crepe, a somber fabric, was used to visually signal the hive was in mourning.

- Funeral Treats (Sometimes): In some variations of the tradition, families went even further, leaving out offerings of funeral cake or wine for the bees. Imagine tiny bees, tipsy on funeral wine… okay, maybe not. But the intention was there – to appease the hive with symbolic treats.

- Funeral Invitations (Seriously!): And in a truly bizarre twist, some families even pinned miniature “invitations” to the funeral on the hive itself. Did they expect the bees to RSVP? Arrive in tiny black carriages? Again, unanswered questions, but you gotta admire the dedication to the superstition, dont you?

Bee-havior Problems: Documented Cases of Funeral “Crashes”

Now, you might be thinking, “Okay, that’s a weird custom, but surely it’s just folklore, right? No actual proof that bees get miffed if they’re not informed of deaths?” Well, here’s where it gets… interesting. Because there are, in fact, documented accounts of bees behaving… let’s just say, less than ideally at funerals where the deceased had beekeeping connections.

These weren’t just whispers and rumors, but actual incidents reported in newspapers and local accounts. Let’s look at a few examples of bee “funeral crashers”:

- 1894 Church Service Chaos: During a funeral held inside a church (imagine the acoustics!), mourners were disrupted by a swarming mass of bees. A pallbearer was stung on the neck (ouch!), and even the undertaker himself was “viciously attacked.” When the funeral procession moved to the graveyard, the bees… followed. Panic ensued, and many mourners, understandably, fled in terror.

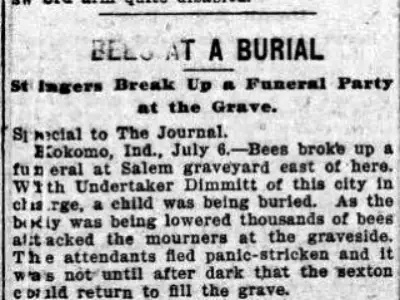

- 1901 Indiana Graveside Attack: A graveside service for a deceased child in Indiana turned into a scene of pure pandemonium. As the coffin was being lowered, “thousands of bees” descended upon the mourners. Complete and utter chaos. They literally had to postpone burying the coffin until nightfall when the bees (presumably) calmed down. Talk about a funeral crasher!

- 1916 Delayed Digging (Thanks, Bees!): Even the simple act of digging a grave for Margaret Culp’s funeral was hampered by bees. Farmers scheduled to dig the grave were “stung severely,” delaying the whole affair.

- Kentucky Gravesite Swarm (Early 1900s): At Josh Simms’ funeral in Kentucky, as flowers were placed on the grave, a “huge swarm of bees” landed on the gravesite. And, you guessed it, they then proceeded to sting numerous mourners who had lingered behind. Not exactly a fond farewell.

What did all these chaotic, bee-sting-filled funerals have in common? The deceased was either a beekeeper or a relative of one. And, crucially, in each case, the bees had reportedly not been told about the death. After these incidents, when the hives were checked… they were often found abandoned. Coincidence? Superstition? Or were these bees just really, really sensitive to household gossip?

Whittier’s “Telling the Bees”: Poetry and Pompus Circumstance

This peculiar bee superstition even buzzed its way into the realm of poetry! In 1858, the American poet John Greenleaf Whittier penned a poem simply titled “Telling the Bees.” It beautifully encapsulates the custom and the melancholic atmosphere surrounding it.

The poem narrates a scene where a young observer watches a “chore-girl” somberly informing the bees of a death in the household. The poem ends with these evocative lines, capturing the essence of the superstition:

Before them, under the garden wall,

Forward and back,

Went drearily singing the chore-girl small,

Draping each hive with a shred of black.

Trembling, I listened: the summer sun

Had the chill of snow;

For I knew she was telling the bees of one

Gone on the journey we all must go!

…

And the song she was singing ever since

In my ear sounds on:–

“Stay at home, pretty bees, fly not hence!

Mistress Mary is dead and gone!”

(You can find the full poem online – it’s worth a read!). Whittier’s poem solidified “telling the bees” in the cultural consciousness, forever linking bees, death, and this unusual, poignant ritual. Poetry cementing superstitions? Now there’s an interesting thought.

Buzzing Away into History: The Legacy of “Telling the Bees”

So, what do we make of all this bee-funeral drama? Is it simply a quaint, if slightly bonkers, piece of folklore? Or is there something more to it? Probably the former, let’s be honest. There’s no scientific evidence that bees actually care if you tell them about Aunt Mildred passing away. And the idea that they’d abandon their hives out of sheer pique or grief? Scientifically unlikely, to say the least.

More likely, “telling the bees” reflects a deeper 19th-century worldview. A world where nature was seen as intimately connected to human life, where superstitions thrived, and where economic anxieties (like losing a valuable honey source) could easily intertwine with folk beliefs. It’s a fascinating glimpse into a time when the line between the natural world and the supernatural felt much, much thinner, isnt it?

While “telling the bees” is largely relegated to history books and quirky trivia now, it serves as a reminder of how deeply ingrained superstitions can become, and how even the smallest creatures – like bees – can be woven into the fabric of our beliefs about life, death, and everything in between. So, next time you see a bee, maybe just… whisper a friendly greeting. Just in case. You never know, do you?